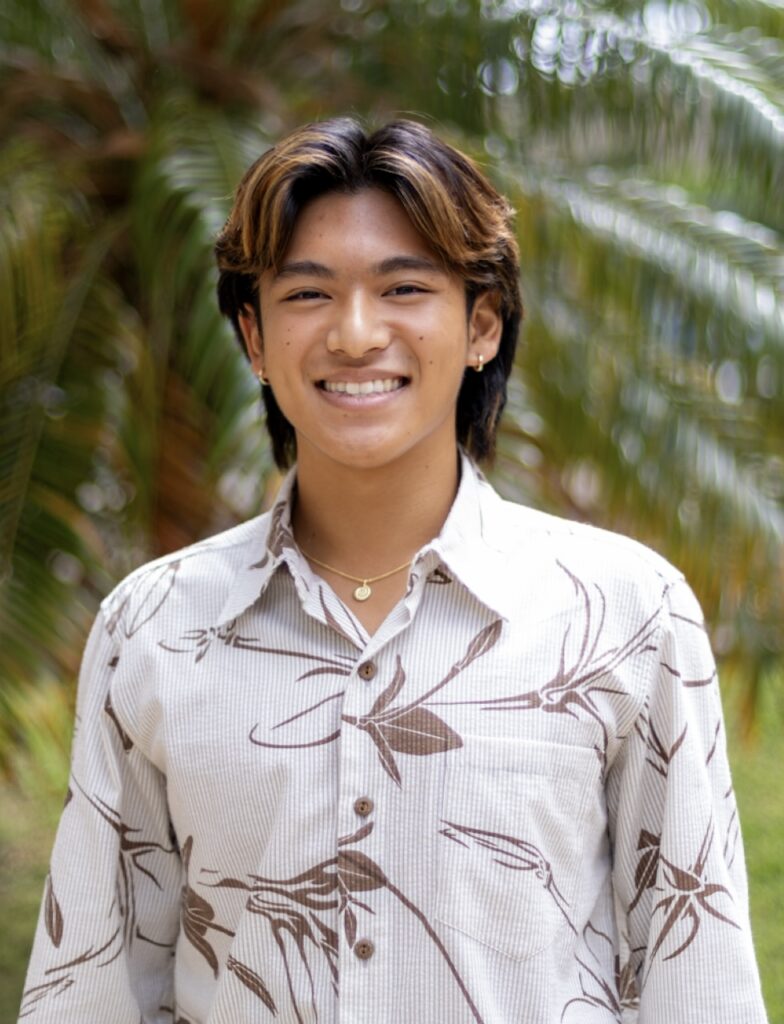

Written by 2025 Champion for Change Joshua Ching, a Kanaka Maoli activist passionate about access to justice issues in Pasifika diaspora communities. A rising senior at Yale University, currently interning with the U.S. Senate, Josh is studying Political Science and Ethnicity, Race & Migration, with a concentration in Native & Indigenous Studies.

As a Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow, Arthur Liman Undergraduate Fellow and an intern with the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, he helped to design and develop an A.I.-based tool to streamline the expungement application process in Hawaiʻi. On campus, he founded the Indigenous Peoples of Oceania at Yale, co-lead the New Haven Pardon Program, worked as a research assistant for Dr. Hiʻilei Hobart and served as Head of House Staff at the Native American Cultural Center. Back home in Hawaiʻi, he’s led several successful political advocacy campaigns.

One year ago—June 11, 2024—I sat in a crowded auditorium hall on the upper floors of the Hawaiʻi Convention Center. Seated to my left and right were people from across Moananuiākea, our grand Pacific, gathering for the quadrennial Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture. Like many others, I marveled at the power of bringing our Pasifika relatives together and bearing witness to – as Fijian scholar Epeli Hauʻofa writes – our sea of islands.

That day marked the beginning of a three-day symposium for the festival, hosted by my alma mater, the Kamehameha Schools. It also coincided with Lā Kamehameha, or Kamehameha Day, a celebration observed annually since 1872. The holiday was proclaimed in recognition of the famed Mōʻī (‘ruler’) who united the Hawaiian Islands under a kingdom in 1810. In the 19th century, celebrations would be marked by festivals and horse-racing. Today, a parade runs annually from ʻIolani Palace to Kapiʻolani Park, and lei-draping ceremonies take place anywhere a statue of the Mōʻī stands.

This Lā Kamehameha, however, I would spend at the opening sessions of this symposium, listening to Pasifika scholars, activists and musicians share about Moananuiākea. That morning, too, I would witness a keynote speech by Hawaiian scholar-activist Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio, which would radically shift my understanding not only of Kamehameha but his enduring legacy of leadership.

Kamehameha Paiʻea, as he was known, was born to Keouakupuapaikalaninui and Kekuʻiapoiwa under the light of Halley’s Comet in Kohala on Hawaiʻi Island. Prophesied to one day overthrow and rule the islands, Kamehameha was reared in secret, tucked in the bosom of Waipiʻo Valley, for his safety. As a young boy, he was raised in the courts of the ruling chiefs Alapaʻinui and Kalaniʻōpuʻu, becoming a skilled and intelligent warrior under their tutelage.

In 1782, a civil war broke out between Kamehameha Paiʻea and his cousin, Kīwalaʻō, after the death of Kalaniʻōpuʻu. Kamehameha, inheriting guardianship of the family’s war god, Kūkaʻilimoku, allied with various chiefs to battle for control of Hawaiʻi Island and, later, the other seven islands in the archipelago. By 1795, Kamehameha had conquered Hawaiʻi Island, Maui, Molokaʻi, Kahoʻolawe and Oʻahu, before negotiating a peaceful transfer of authority over Kauaʻi and Niʻihau.

As an elementary schooler at Kamehameha Schools, I was raised with the moʻolelo (‘stories’) of Kamehameha Paiʻea’s campaign to unite the islands, and the deep spirituality that drove his triumph. I learned Kamehameha would become one of the first aliʻi to encounter foreigners on Hawaiʻi’s shores, with the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1778, which spurred the rapid spread of Western death and disease in the islands. The Mōʻī, in this way, was caught in the shifting tides of Hawaiian history, necessitating a form of leadership that could both unite a people and ward off the impending threat of imperialism.

Dr. Osorio, in her recounting of Kamehameha’s legacy, articulated the Mōʻī’s actions in the immediate aftermath of unification. All of the lands across Hawaiʻi reserved for his war god, Kū, she said, were transformed into Puʻuhonua, our traditional places of refuge. Within the walls of the Puʻuhonua, those who transgressed the ruling powers would be forgiven and offered sanctuary from punishment. These places of refuge, as Osorio argues, were viewed by Kamehameha as a necessary component of a pono (‘righteous and balanced’) society. “While violence and war were certainly present in the time before foreigners,” she said, “violence itself did not legitimize power. It only momentarily consolidated it.”

Where Western systems of governance have long relied on institutions of punishment—like policing, prisons, and military occupation—to legitimize State rule, Hawaiians understood that long-term political legitimacy could only come from cosmological balance, from reconciliation. In her seminal text Nānā I Ke Kumu, famed Hawaiian scholar Mary Kawena Pukuʻi (1972) writes of the importance of forgiveness in our culture, through the concept of kala:

“Hawaiian mores specified both [in a transgression] must forgive—and go beyond forgiving. Both must kala. Each must release himself and the other of the deed, and the recriminations, remorse, grudges, guilts and embarrassments the deed caused. Both must “let go of the cord,” freeing each other completely, mutually and permanently. This was kala, a concept and an ideal.” (p. 75)

This notion of kala, I believe, informed how Kamehameha Paiʻea governed. Nowhere is this more apparent than the first law the Mōʻī decreed for the Hawaiian Kingdom, Ke Kānāwai Māmalahoe, or the Law of the Splintered Paddle. Across several tellings of the moʻolelo of Māmalahoe, a young Kamehameha chased after a group of Puna fishermen before falling into a rock fissure and being struck by one of them in the head with a paddle. After being freed with the help of his steersman, Kamehameha feared the chiefs who surrounded him would demand the slaughter of the people of Puna for his own negligence. He then decreed Ke Kānāwai Māmalahoe, declaring that the innocent and defenseless shall be safe to lie by the roadside without fear of harm, protecting his people from the abuse of chiefly power. Today, Ke Kānāwai Māmalahoe is remembered as Hawaiʻi’s first human rights law, still enshrined in the Hawaiʻi State Constitution.

Beyond the political and legal institutions he constructed, Kamehameha Paiʻea was a Mōʻī who understood his kuleana (‘responsibility’) to his people. Dr. Osorio spoke of how Kamehameha “has been known to enter into the loʻi [taro patch] besides his common people, to crawl behind his high-ranking sons and grandsons, and to struggle over the moral and religious compass of his aupuni [kingdom].” As a student at Kamehameha Schools, I was reminded constantly of the value of alakaʻi lawelawe (‘servant leadership’), which our namesake embodied. Leadership, I was told, was about how one chose to levy their kūlana (‘position’) in service of the people they governed—not out of self-interest, but out of an interest for collective prosperity. It is our kuleana, as young Hawaiians, to serve our lāhui, our Hawaiian nation.

For me, these lessons provoked deep ruminations about the shape and meaning of sovereignty in Hawaiʻi and beyond. Contrived and precarious notions of State-based sovereignty, which root the Western world, has given rise to a model of government that relies on violence and punitivity for its legitimacy. “As we watch genocides play out in West Papua and Palestine,” Dr. Osorio reminds us, “we must come face to face with these violences, not as exceptions or aberrations to sovereignty, but instead as essential components of its imperial design.” She points, instead, to Hawaiian conceptions of Ea, which tells us that our sovereignty does not come from the State, but from the life of the land itself.

As a high schooler at Kamehameha Schools, I bore witness to ea while at the base of Mauna a Wākea, where our lāhui consecrated a Puʻuhonua in defense of our sacred mountain from the construction of a Thirty-Meter Telescope, an expression of self-determination rooted in a deep love for the land. As a college student at Yale University, I bore witness to ea when Indigenous students from across the East Coast gathered together, in shared longing for our homelands, for our biennial Pasifika Fest, a celebration of the shared cultures and practices that constellate Moananuiākea. On June 11 last year, I felt ea in the presence of my relatives from across Oceania, united in a conviction to build and rebuild lasting pilina, or intimacies, with each other.

This year, I will spend my Lā Kamehameha in the heart of Washington, DC, working for my Congressional Delegation. Amid ongoing threats to Native Hawaiian and tribal sovereignty, federally-funded Indigenous-serving programs, and crucial access to social services for communities across Hawaiʻi and Indian Country, I am reminded of the importance that leaders like Kamehameha Paiʻea hold, here and now more than ever. While chaos, confusion, and egoism characterize the shape of ‘leadership’ at the national level today, I am clinging tight to the wisdom of reconciliation, the strength of forgiveness and the value of genuine security for all. Propelled by the legacy of Kamehameha Paiʻea, it is time to (re)member our kuleana and kūlana, our responsibility and our place, to each other.

Democracy is Indigenous

Democracy is Indigenous