Beauty All Around Us: A Reflection on Storytelling, Food & Youth-Led Futures

Written by Tommey Jodie, a Diné student, poet and community-based researcher from Teesto, AZ. Currently pursuing degrees in Creative Writing, Food Studies, and Nutrition & Food Systems at the University of Arizona, Tommey’s work is grounded in the interconnectedness of land, food and identity. She is passionate about Indigenous food sovereignty, community care and storytelling, drawing inspiration from her upbringing in the Southwest, rodeo and Diné teachings, which continue to shape her work as both an artist and advocate.

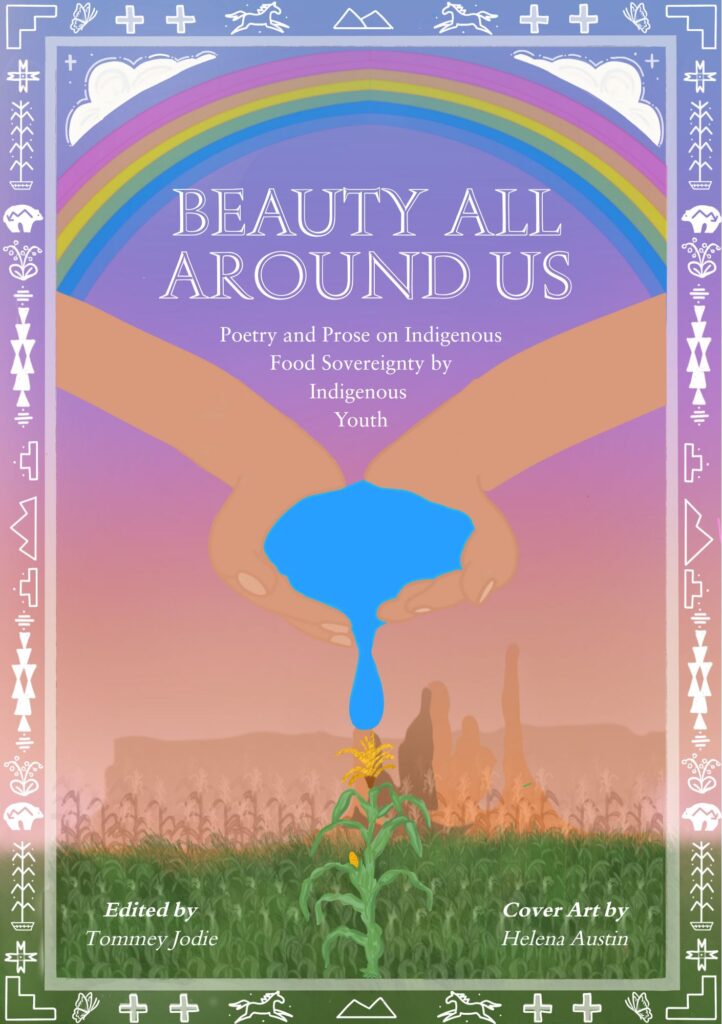

When I began this project, I set out with a vision: to combine Indigenous food sovereignty and storytelling into something tangible. I wanted it to be more than an academic exercise. It needed to reflect who we are and what we carry as Indigenous people. At first, it was just my senior capstone but, as it evolved, it became something far more communal, emotional and deeply affirming. Beauty All Around Us is the name of this zine, but it’s also a truth that my people, the Diné, have always known. There really is beauty all around us—in our languages, our land, our memory and especially in the voices of Indigenous youth.

I’ve spent the last few years studying global food systems and the impact of settler colonialism on Indigenous lifeways. But I’ve also been writing poetry, learning from my community and listening to youth who are already creating the futures we talk about.

This zine exists at the intersection of all of those things: it’s research, memory, resistance and love. Featuring original poetry and prose from 15 Indigenous youth from tribal nations across the so-called United States, the zine explores food, gender, ceremony, land, kinship and longing—not as aesthetic, but as truth. These pieces don’t just talk about Indigenous food sovereignty—they live it. They embody it.

Editing this zine was never just about managing submissions or organizing content. It was about holding space. I stayed up late formatting pages, emailing contributors and helping those who needed design support. I wanted the process to be open-hearted, flexible and grounded in care. Every contributor was between 19 to 25-years-old and, for many, this was their first time being published. Even though the zine is intertribal, I felt a deep sense of home in their words. I saw k’é—the Diné principle of relationship and reciprocity—flowing throughout every page. This zine also shows that Indigenous food sovereignty can and will look different across Indigenous nations and territories based on their own unique needs. These stories are medicine. They are teachings. They are tangible proof of the brilliance that our Indigenous youth carry.

Throughout the process, it’s been important to me to express how central storytelling has always been to Indigenous food sovereignty. Our ancestors didn’t just pass down stories to entertain—they used them to guide, to instruct, to nourish. Poetry, in particular, has always existed in our cosmologies, our songs and our ceremonies, even if it wasn’t named as such. As Diné, I was taught that food is sacred and that when we eat traditional foods, we are not only feeding our bodies—we are feeding a history, a people. The land teaches us. Our language carries us. And through writing, we resist settler colonial paradigms that attempt to erase that knowledge. This project helped me understand that more clearly than ever.

One of the most powerful parts of this experience was seeing Indigenous youth centered not as tokens, but as the driving force—the heartbeat of this project. Our contributors didn’t just write about food—they wrote about survival, autonomy and liberation. Their work critiques capitalism, environmental degradation and settler colonial violence, all of which continue to shape the current industrial food system and disproportionally target marginalized communities. Their writing and Indigenous presence in the writing world also offers hope. It reminds us that Indigenous youth are not waiting to be given space. They are making it themselves.

This zine also showed me just how much labor goes into Indigenous food sovereignty projects—and how little structural support exists for them. I relied on crowdfunding to pay our Native youth illustrator and cover printing costs. Still, this project reached over 100,000 people during our call for submissions through a collaborative post with NDN Girls Book Club and is now being published by Abalone Mountain Press, a Native woman-owned press. Free printed copies are also being distributed to Indigenous student centers, youth programs and community organizations. That’s the power of Indigenous-led work—it ripples outward even when resources are limited.

If I’ve learned anything from this process, it’s that Indigenous food sovereignty is not just about food. It’s about memory. It’s about art. It’s about story. It’s about the right to define and sustain life on our own terms. Indigenous youth are doing that every day—and this zine is just one small space where that brilliance can be held. As Indigenous people, we already hold the knowledge we need to build futures where Indigenous people are not just included but leading them. As Diné activist Klee Benally (2023) emphasizes in No Spiritual Surrender, it was not settler politics or government aid that brought Diné people home after The Long Walk of 1863—it was ceremony and collective action. Resistance cannot be done alone; it must be done collectively and communally.

I want to thank NDN Girls Book Club, whose microgrant helped make this zine possible. I also want to thank every community member, friend and relative who donated, supported or simply believed in this work. This project wasn’t built in isolation. It was built with community, and that’s what gives it life. And to every contributor: thank you. This zine belongs to you. And to every Native youth reading this—your stories matter. Keep telling them. Keep planting. Keep dreaming.

T’áá hwó’ ají t’éego.

If it’s up to anybody, it’s up to you.

If you want to access the digital version (free) of Beauty All Around Us, it can be found on CNAY’s website here or Abalone Mountain Press’ Issuu here. If you want to purchase a printed copy of Beauty All Around Us, you can purchase here and 100% of the funds go back into future reprints to distribute for free to Native communities. If you want to request free copies of Beauty All Around Us for your organization, the form can be found here.

—

At the Center for Native American Youth (CNAY), our mission is to improve the health, safety and overall well-being of Native American youth. We work for and with Native youth like you to ensure you have the opportunity to drive your own narrative focused on your strengths, culture and the positive things you do every day.

To be featured on our digital platforms, please complete the CNAY Youth Highlight Form. To date, our social channels – including Facebook, X (Twitter) and Instagram – have a reach of more than 35,000 followers. You can use this form to highlight your solutions to challenges facing your community, showcase your culture, or amplify your latest project, activity or event.

Are you part of a youth council or student group? Show us your work! Do you have an opinion on environmental justice that you want to share? Work with us on a featured blog! Do you want to be a role model for other Native youth? Let us feature you! We can also help you grow skills on social media, writing blogs, interviewing or creating digital content. Questions? Contact Jamie Levitt: jamie.levitt@aspeninstitute.org

Democracy is Indigenous

Democracy is Indigenous